Architecture professor’s new work examines enclosed, air-conditioned spaces

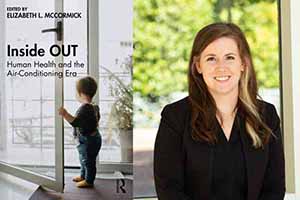

A new book edited by Assistant Professor of Architecture Liz McCormick considers the many impacts of air conditioning on the built environment and on human health and behavior.

“Inside OUT: Human Health and the Air-Conditioning Era,” published this spring by Routledge Press, presents an interdisciplinary, holistic analysis of the social, behavioral, and technological issues of air-conditioned indoor space.

“In this extraordinary book, McCormick and collaborators help us to understand the new environment we have created, indoors, from the perspectives of history and architecture,” said Rob Dunn, a biologist and author of “A Natural History of the Future.” “If you would like to understand the spaces in which you spend nearly all of your waking and sleeping hours, how they affect you and how they came to be the way they are, read Inside OUT.”

McCormick says that while she has long been interested in the connections between buildings and human health, she began to focus intently on the enclosed environment of fully conditioned buildings during the COVID-19 pandemic, “when buildings became the enemy of respiratory health.” And even though the sudden awareness of air-borne viruses led people to open more windows and spend more time outdoors, most people in the United States still spend 90% of their time inside, where contamination — from people and from products like building materials, furniture, or cleaning chemicals — gets trapped.

“Indoor air is not regulated in the U.S. It’s not even tracked,” McCormick said. Except in unusual cases such as wildfires or high ozone days, “outdoor air is cleaner,” she added.

McCormick grew up in steamy Houston, Texas, and knows the positive value of air conditioning, but she also has witnessed its negative implications — on architectural design, environmental sustainability, and human health and behavior.

For example, fully conditioned buildings have contributed to a homogeneity of design that reduces the distinctiveness of regional architecture.

“You lose some of the spirit of the cities,” McCormick said.

And spending so much time in tightly controlled temperatures has affected perceptions of what is comfortable.

“As people get more and more used to air conditioning, what we can tolerate has narrowed.”

The burden on the electrical grid — and thus the health of the environment — has been well documented. Then there are the effects on human health.

“There are more cases of allergies and asthma in developed countries than in less developed countries,” she said.

In the book, McCormick and her contributors, Sarah Haines, Marcel Harmon, Z Smith and Ulysses Sean Vance, consider both the past and the present to understand how practices and perceptions have been shaped.

“There is a lot of archival imagery in the book used to convey how our views of the indoors are deeply rooted in historical social constructs of comfort, health, and hygiene,” McCormick said.

To read the entire article, visit the College of Arts + Architecture website at https://coaa.charlotte.edu/news/2024-05-17/professors-new-book-examines-implications-enclosed-air-conditioned-spaces