SOLVING THE INSOLUBLE

Engineering graduate Jordan Landis ’24 spearheads researching the use of microplastic-eating algae to improve Charlotte’s wastewater treatment — and America’s overall water quality

Written by: Phillip Brown

Photos by: Amy Hart

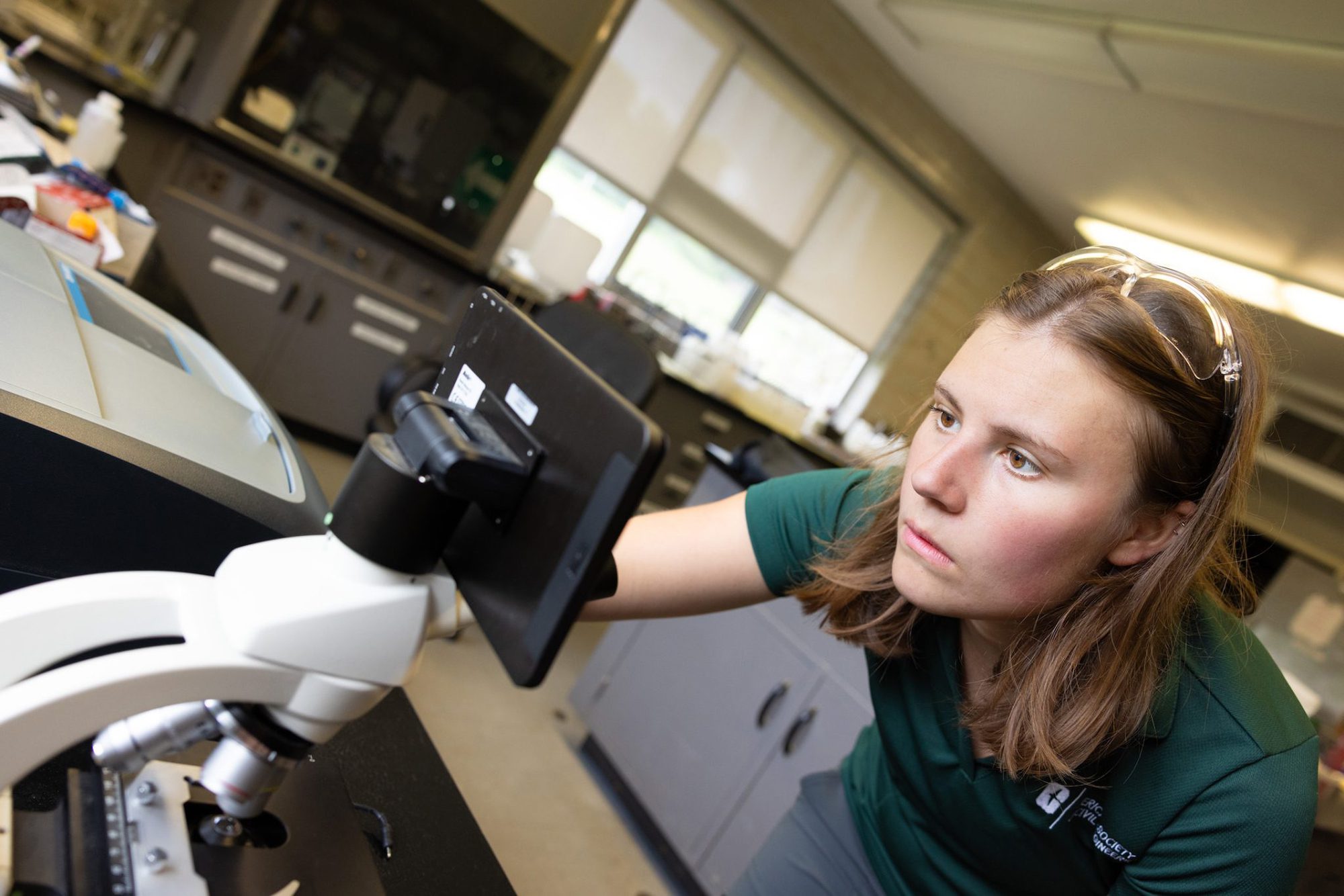

Jordan Landis ’24 takes a hard look at a water sample before placing it under a microscope to examine. Despite its clear appearance, she suspects the powerful lens will reveal much more.

As Landis anticipates, microplastics — nanosized pieces of plastic — show up in the sample. More and more frequently, microplastics are finding their way into all water sources — in nature and at wastewater treatment plants. This is problematic for people and communities, including Charlotte.

“Water affects us all. Everyone needs clean, potable water, so that drives my desire to work in sustainable infrastructure and environmental engineering,” said Landis, who after completing a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering in May, dove into doctoral studies at the University of Michigan in fall 2024.

While at Michigan, she is continuing a partnership with Charlotte Water on a potentially groundbreaking advancement to mitigate microplastics at wastewater plants before returning treated water to the environment.

Power of partnerships

Muriel Steele, a wastewater process engineer at Charlotte Water, says the city of Charlotte is fortunate to have a great research university at its disposal. As Landis’s internship supervisor, Steele recognizes the impact UNC Charlotte’s research capabilities can have on the Queen City and beyond.

“It’s an obvious partnership. We like to support students by exposing them to the industry before they leave college. And it allows Charlotte Water to engage in more proactive research,” she explained. “We conduct measurements and standardized tests to ensure compliance, but it’s important to have a research university to enable us to try new methods and analytical techniques.”

“The city of Charlotte is fortunate to have a great research university. It’s an obvious partnership. We like to support students by exposing them to the industry before they leave college. And it allows Charlotte Water to engage in more proactive research.”

-Muriel Steele

Landis also touted the impact of partnerships between the community and the University.

“Charlotte Water has been instrumental in the ongoing efforts related to the Charlotte Algae Microplastic System,” she said. “From the outset, the utility was very receptive. I can’t imagine we would have been able to garner the same support in a smaller municipality.”’

The Charlotte Algae Microplastic System uses bioengineered algae to “eat” microplastics in the water while being treated at wastewater facilities. Landis has a patent pending on the system.

What are microplastics, and what are the concerns?

‘Everyone needs clean, potable water, so that drives my desire to work in sustainable infrastructure and environmental engineering.’

-Jordan Landis

Plastic pollution is a growing threat to human health, with billions of plastic items choking streams, lakes and oceans. Each year, the average American ingests more than 70,000 microplastics through their drinking water supply.

Microplastics can come from synthetic fibers, tires and virtually any plastic product that degrades over time. Plastic microbeads, such as those found in cosmetics and personal care products, add to the problem. To date, the only national regulation to limit microplastics is the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 that prohibits their use in products sold in the United States.

The effects of microplastics on human health is an emerging field of study, but hazards of ingesting plastic particles by wildlife include digestive obstruction, impaired reproduction and other adverse biological functions leading to death.

Seeking solutions to improve wastewater treatment

Landis, as an undergraduate in the William States Lee College of Engineering, co-led a student research team with Justin Sprumont ’24 to tackle the issue of microplastics in the water supply as part of a national innovation competition for the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The team proposed using bioengineered algae to treat wastewater effluent to remove microplastics and nanoplastics. This approach won the competition and attracted the attention of Charlotte Water’s Steele, who attended a presentation on the team’s project and saw real-world potential.

“Charlotte Water adheres to strict state and federal standards for treatment, but microplastics are a global water issue and a concern for which we recognize the need to be proactive,” said Steele. “Microplastics aren’t regulated currently, so we are focused on exploring this issue to be at the forefront of water treatment in an effort to protect our customers and communities.”

Charlotte Water’s Muriel Steele describes Jordan Landis a “go-getter” who is passionate about the environment.

Prior to the national ASCE competition, Landis began reviewing various scientific approaches to plastics in water, and she discovered researchers in the Far East had identified bacteria that produced an enzyme that could break down plastic in landfills. She also learned of studies using bioengineered forms of the algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Landis and her team worked with experts to identify bioengineered versions of the algae, which had the DNA of the bacterial enzyme that could break down plastic inserted as part of its photosynthesis process.

“While the algae grow, it produces more of the enzyme to consume the plastic,” explained Landis. “Plastics are polymers or chains of molecules that are combined chemically. The bioengineered algae break these polymers into monomers or single molecules that are more benign to the environment.”

Landis gathers a sample from one of Charlotte Water’s wastewater treatment facilities.

While pursuing a Ph.D., Landis will continue to intern with Charlotte Water to quantify the success of her research. She and the ASCE innovation team have a pending patent on the Charlotte Algae Microplastic System, and they are seeking additional funding from the National Science Foundation to further proof of concept.

Charlotte Water’s Steele said additional research is needed, but “the process could be applied commercially not just in Charlotte but nationwide with implications for wastewater treatment plants and other large industries that work with plastics.

“Jordan is a real go-getter,” Steele added. “She’s incredibly passionate about the environment, and it really drives her to work hard.”

All in for research

A graduate of Riverside High School in Durham, Landis ran cross country in high school and was recruited by Charlotte 49ers Athletics. Recurring injuries led her to focus on academics and research.

As a runner, she is drawn naturally to the outdoors, and in high school, she was part of Project Lead the Way, which offered special learning opportunities for students interested in STEM fields.

But her interest in science started at an even earlier age. Her father, Matthew, is an air quality researcher with the Environmental Protection Agency, and during her childhood, he would take her to his lab in Research Triangle Park.

“He has an atmospheric lab and studies the effects of forest fires, and he would show me how the radars worked, so I really became interested in meteorology,” said Landis. Gradually, her focus shifted toward water quality, studying how agricultural runoffs in watersheds could affect public health. She also followed the well-known water crisis in Flint, Michigan, as an example of how low income communities are affected by poor water quality.

While being recruited for track, Landis met with the engineering college’s director of undergraduate programs, William Saunders. She came away convinced that Charlotte provides a student-centered learning environment designed to help her succeed.

“He stressed the wide variety of engineering disciplines the college offered and that I would gain exposure to them all, but mostly, I walked away from the meeting feeling like I would be supported, which was key to my decision.”

“I want to pursue a nature-based approach, bridging earth sciences and engineering to design real-world solutions that will combat society’s huge issues.”

-Jordan Landis

Landis examines a sample in a Charlotte engineering labs. Her interest in science started early; in high school, she was part of Project Lead the Way, which offers learning opportunities in STEM fields for interested students.

Beyond opportunities with the college, Landis interned with the University’s Office of Undergraduate Research, where she assisted Sandra Clinton, a research associate professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Geographical Sciences. Clinton studies how urban beaver ponds function compared to human-made stormwater ponds in maintaining the health of urban streams. Landis took advantage of the opportunity to study microplastic concentration in these environments.

“I definitely saw a higher-than-expected number of microplastics in the field,” said Landis, adding her robust undergraduate research experiences have fueled her desire to make a difference. “I want to pursue a nature-based approach, bridging earth sciences and engineering to design real-world solutions that will combat society’s huge issues. Charlotte is one of few engineering programs that offer this perspective.”

RELATED CONTENT

Jordan Landis is testing the waters. Literally.

Jordan Landis focuses the microscope to get a better view of particulates that are magnified 100x beneath the lens. She is not surprised to find multiple pieces of debris in the 1ml water sample.