Machine learning meets mesocyclones: Ian Shank’s summer of storms

Ian Shank, a senior meteorology student, was driving a packed car to Norman, Oklahoma, to be a student researcher at the National Weather Center for the summer, when the skies above him started to darken.

Shank and his mother were on one of the final legs of their journey when a moderate risk for severe weather was issued in Arkansas.

After trying to outrun the storm, they stopped in Fort Smith, Arkansas, on the border of Oklahoma. However, the hotel they planned to stay at lost power, forcing them to wait in a nearby diner. Suddenly, they were surrounded by massive storm clouds.

“My meteorology senses were tingling,” Shank said.

Suddenly, nearby phones started going off — a tornado warning had been issued. As the storm grew, Shank worried the diner would lose its roof or softball-sized hail would dent his car.

“Oh, so this is what the next three months are gonna be like,” thought Shank, as he and his mother huddled with other diner patrons in the women’s bathroom.

From his studies, he knew the space offered safety, but he didn’t feel the need to share that information in such an overwhelming moment.

“I knew that after the squall line and the leading edge came through, we were safe because there was no warm air to help produce a tornado or cause tornadogenesis,” Shank recalled of the storm.

However, his mother took the opportunity to tell the others what her son studied and where he was headed. Reluctantly, Shank explained how the group was scientifically safe, there, inside a women’s bathroom, in Arkansas.

A Lifelong Weather Enthusiast Arrives at the Mecca

Shank and his mother share a close bond, and she knew he would grow up to be a meteorologist. In 2013, while visiting grandparents in Pennsylvania, Shank watched the television as a severe storm ripped through his hometown of Albemarle, North Carolina. The storm extended the family’s trip and made Shank curious how these systems work.

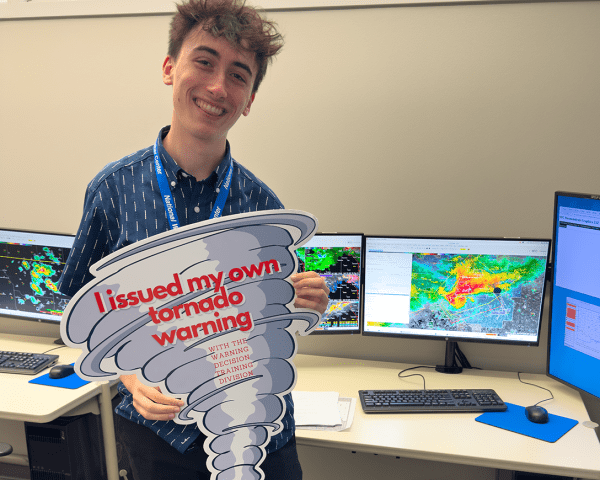

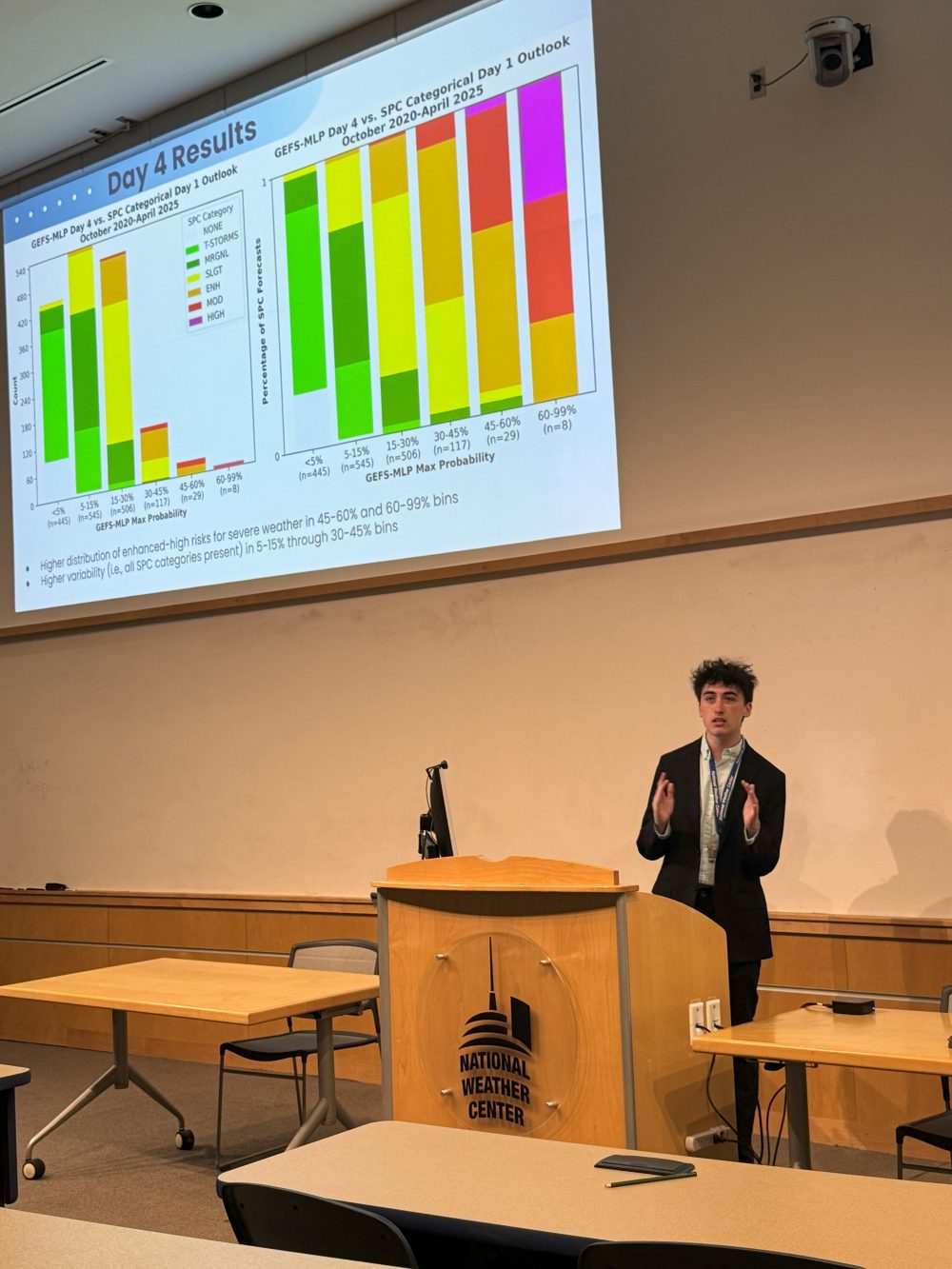

Fast forward a decade, Shank was arriving at the National Weather Center, where he would be researching machine learning models used by professional meteorologists to predict the severity of storms. Shank was excited to dive into this program because he wanted to be on the cutting edge of where the industry was headed.

During the internship, Shank and his team pored over years of weather data to identify signals within the machine learning probabilities that indicate a severe weather event will occur. They also examined biases in the data related to population density. He rubbed shoulders with meteorologists and climatologists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But the most breathtaking feature of the National Weather Center was the enclosed weather observation deck at the top of the building.

“If there was a storm in Dallas, we could see it; if there was a storm in Amarillo, Texas, we could see it; if there was a storm in Wichita, Kansas, we could see it,” Shank said. “It was incredible.”

The Craziest Weather Day of My Life

On Tuesday, June 3, the Norman area was issued an enhanced risk for severe weather from the National Weather Center. Shank knew he had a good chance of seeing a severe weather event during his internship. Little did he know, he would witness two mesocyclone formations — the precursor to a tornado — on the same day.

Shank was in a room with members of his research cohort and professional Weather Service forecasters. Off in the distance, he noticed a lowering of the clouds and a slight rotation indicating the start of a mesocyclone. He then checked the radar velocity and confirmed it was indeed spinning.

“For a split second, there was a little funnel cloud and immediately 10 of the people that were in that room ran downstairs,” Shank recalled. “About 30 seconds later, there was a tornado warning issued.”

After the tornado warning was issued, sirens began to sound — a bit of a shock for the North Carolina native.

Since there was no covered parking at the National Weather Center, Shank decided to move his car to the garage at his apartment complex. As he drove, a giant, pitch black wall chased him. He slammed on the accelerator.

“In North Carolina, very rarely am I scared that an EF5 tornado is going to come barreling toward me,” Shank said. “But here, that’s a distinct possibility.”

He started to run inside when he looked up and saw a sight he would never forget — a rapidly-spinning, massive tornado that touched down in Norman, just five miles away.

“You know, it’s bad when the Oklahomans run inside,” Shank said.

Paying Connections Forward

Shank initially connected with the University of Oklahoma and the National Weather Center at the American Meteorology Society conference — an annual event attended by UNC Charlotte meteorology juniors — in New Orleans. Meteorology professors advised Shank and other Charlotte students to make the most of the networking opportunity.

After spending three months in Norman — conversing with professionals and chasing storms with fellow interns from around the country — Shank has an even greater appreciation for networking.

“The biggest thing that I learned this summer is probably how important your connections are,” Shank said. “I feel very blessed and honored to have had this opportunity, because there isn’t a better place in this country to form meteorology connections than the National Weather Center.”

As the secretary of Storm Club, Shank plans to leverage the connections he made this summer to secure guest speakers, enhancing the experience of meteorology students at UNC Charlotte.

“I don’t want to keep what I’ve experienced this summer to myself,” Shank said. “I want to help provide a better experience. It’s my last year at Charlotte, so I want to make sure that I give everyone the same opportunity to build connections.”